“Notice what we have already seen”

-Alain de Botton

It was completely and utterly serendipitous…

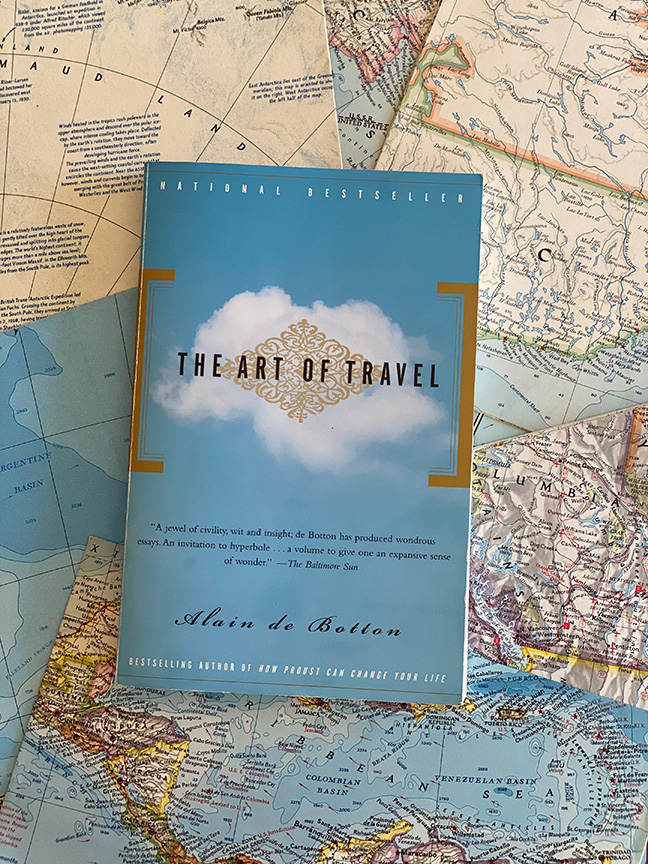

Monday night having arrived in East Hampton to settle in for my own self quarantine I grabbed some books to put by my bedside. It was a random selection of a couple books to reread, a collection of essays and Alain de Botton’s THE ART OF TRAVEL. Ironic right? Reading about travel when it is far from being an option. What made me hand select THAT book, a book I read some time ago, who knows.

The style of de Botton a ‘flaneur’, his enthusiasm for travel, his attention to detail, his affinity for Wordsworth, Baudelaire, and Alexander von Humboldt and all of their peregrinations makes for a read that draws you deeper and deeper.

So, having read this before I selected this chapter on HABIT, also ironic as if ever there was a time our habits would be broken this would be the time. There lying in wait was the story of Xavier de Maistre and his tour around his bedroom, his room travel.

READ ON BELOW HERE, then go buy the book if you have not read it.

Now is the time for armchair travel. Now, room travel is de riguer.

Excerpt from THE ART OF TRAVEL:

From 1799 to 1804, Alexander von Humboldt undertook a journey around South America, later entitling the account of what he had seen Journey to the Equinotical Regions of the New Continent.

Nine years before Humboldt set out, in the spring of 1790, a 27-year- old Frenchman named Xavier de Maistre had undertaken a journey around his bedroom, an account of which he would later entitle, Journey around my Bedroom. Gratified by his experiences, de Maistre in 1708 embarked upon a second journey.

Xavier de Maistre was born in 1763, in the picturesque town of Chambery, at the foot of the French Alps. He was of an intense romantic nature and was fond of books, especially Montaigne, Pascal and Rousseau, and of paintings, above all Dutch and French domestic scenes. At the age of 23, de Maistre became fascinated by aeronautics. In 1790, while he was living in a modest room at the top of an apartment building in Turin, de Maistre pioneered a mode of travel that was to make his name; Room travel.

In 1790, while he was living in a modest room at the top of an apartment building in Turin, de Maistre pioneered a mode of travel that was to make his name; Room travel.

‘Millions of people who, until now, have never dared to travel, others who have not been able to travel and still more who have not even thought of traveling will be able to follow my example,’ explained Xavier.

The story begins well: de Maistre locks his door and changes into his pink and blue pajamas. With no need of luggage, he travels to the sofa, the largest piece of furniture in the room. His journey having shaken him from his usual lethargy, he looks at it through fresh eyes and rediscovers some of its qualities. He admires the elegance of its feet and remembers the pleasant hours he has spent cradled in it’s cushions, dreaming of love and advancement in his career. From his sofa, de Maistre spies his bed. Once again from a travelers vantage point, he learns to appreciate this complex piece of furniture. He feels grateful for the nights he has spent in it and takes pride in the fact that his sheets almost match his pajamas.

De Maistre’s work sprang from a profound and suggestive insight: the notion that the pleasure we derive from a journey may be dependent more on the mind-set that we travel with than on the destination we travel to. If only we could apply a traveling mindset to our own locales, we might find these places becoming no less interesting than, say, the high mountain passes and butterfly field jungles of Humboldt’s South America.

What, then, is a traveling mindset? Receptivity might be said to be its chief characteristic. Receptive, we approach new places with humility. We carry with us no rigid ideas about what is or is not interesting. We irritate locals because we stand in traffic islands and narrow streets and admire what they take to be unremarkable small details. We risk getting run over because we are intrigued by the roof of a government building or an inscription on a wall. We find a supermarket or hairdressers shop unusually fascinating. We dwell at length… We are alive to the layers of history beneath the presents and take notes and photographs.

Home, by contrast, finds us more settled in our expectations. We feel assured that we have discovered everything interesting about our neighborhood, primarily by virtue of our having lived there a long time. It seems inconceivable that there could be anything new to find in a place where we have been living for a decade or more. We have become habituated and therefore blind to it.

De Maistre tried to shake us from our passivity. In his second volume of Room Travel, Nocturnal Expedition around My Bedroom, he went to his window and looked up at the night sky. Its beauty made him feel frustrated at such ordinary scenes were not more generally appreciated: ‘How few people are right now taking delight in this sublime spectacle that the sky lays on uselessly for dozing humanity! What would it cost for those who are out for a walk or crowding out of the theater to look up for a moment and admire the brilliant constellations that gleam above their heads?’

There are some who have crossed deserts, floated on ice caps and cut their way through jungles but whose souls we would search in vain for evidence of what they have witnessed. Dressed in pink and blue pajamas, satisfied within the confines of his own bedroom, Xavier de Maistre was gently nudging us to try, before taking off for distant hemispheres to notice what we have already seen…

A little bit about de Maistre: A parody set in the tradition of the grand travel narrative, ROOM TRAVEL is an autobiographical account of how a young official, imprisoned in his room for six weeks, looks at the furniture, engravings, etc., as if they were scenes from a voyage in a strange land. He praises this voyage because it does not cost anything, and for this reason it is strongly recommended to the poor, the infirm, and the lazy. His room is a long square, and the perimeter is thirty-six paces. “When I travel through my room,” he writes, “I rarely follow a straight line: I go from the table towards a picture hanging in a corner; from there, I set out obliquely towards the door; but even though, when I begin, it really is my intention to go there, if I happen to meet my armchair en route, I don’t think twice about it, and settle down in it without further ado.”

The Art of Travel

Alain de Botton

Click here to buy the book!

The results of some of Charlotte’s room travel are in C’est inspire, click here to see!

March 18, 2020